Silver hit $120 per ounce in late January—a record that lasted eight trading days. By February 3, it had collapsed to $89, a 26% drawdown that erased weeks of gains and left the iShares Silver Trust posting its worst single-week loss on record. Gold, meanwhile, rallied 5% in the same window, with the SPDR Gold Shares climbing after a brutal 10% weekly decline. The metals markets are supposed to move together in crisis. They’re not. And that divergence—silver cratering while gold rebounds—signals something more destabilizing than a commodity correction: the safe haven framework itself is fracturing under the weight of overlapping crises that defy historical playbooks.

The traditional script says precious metals rally when confidence in fiat currency erodes. Inflation fears, geopolitical instability, central bank overreach—these are the textbook triggers. But February 2026 is offering a different lesson. The Federal Reserve held interest rates steady at 3.5–3.75% on January 29, defying President Trump’s public calls for aggressive cuts. Fed Chair Jerome Powell, whose term expires in May, described Trump’s Justice Department investigation into him as a “pretext” for political pressure. The dollar strengthened on the news. Gold, in theory, should have weakened. It didn’t. It climbed.

The mechanics are inverted because the crisis isn’t monetary debasement—it’s institutional fragility. When the independence of the world’s most important central bank is openly contested, when a sitting president captures a foreign head of state in a military operation condemned by the UN as a violation of international law, when China’s rare earth export controls create supply chain anxiety despite a temporary suspension, the question isn’t whether fiat currencies will inflate. It’s whether the institutional architecture that gives those currencies meaning will hold. Gold is rallying not as an inflation hedge but as a sovereignty hedge—a bet that when legal norms collapse, the only reliable store of value is the one that doesn’t depend on institutions functioning.

Silver’s collapse tells the inverse story. Silver is an industrial metal masquerading as a monetary one. Roughly half of global silver demand comes from electronics, solar panels, and manufacturing—sectors acutely sensitive to economic growth expectations. The metal broke $100 in late January on speculation that industrial demand would remain robust even as financial uncertainty drove safe-haven flows. That thesis lasted until investors remembered that geopolitical chaos and robust industrial activity rarely coexist. The U.S. intervention in Venezuela, regardless of its stated objectives, introduces a new variable into Latin American stability calculations. Software stocks—ServiceNow, Salesforce, Adobe—are hitting 52-week lows in their sixth consecutive session of declines, a signal that corporate spending is contracting. When the growth outlook darkens, silver loses its dual mandate. It’s not rare enough to be pure money, and it’s too tied to economic activity to be a true safe haven.

The dollar, meanwhile, is behaving like a geopolitical weapon rather than a reserve currency. It strengthened following the Venezuela operation—not because U.S. economic fundamentals improved, but because investors are pricing in a world where the dollar’s value derives less from trade flows and more from its role as the denominator of coercive power. Treasury yields are sending mixed signals: the 10-year sits near multi-month highs, reflecting concerns about fiscal sustainability, yet demand for short-term bills remains strong as investors park capital in the safest available asset while waiting for clarity. The yield curve is inverted, a recession signal, but the inversion is driven by policy uncertainty rather than overheating.

So which safe haven actually works? The answer depends on what you’re seeking safety from. If the threat is inflation—traditional money printing, fiscal dominance, central bank capitulation—Treasuries remain the paradoxical best bet. The Fed may be under political pressure, but it has not yet printed money to finance deficits, and the bond market continues to price U.S. credit risk as negligible despite rising debt levels. Inflation-indexed TIPS offer positive real yields for the first time in years.

If the threat is institutional breakdown—the erosion of central bank independence, the weaponization of international law, the collapse of multilateral trade frameworks—gold makes sense. It’s the only major asset whose value doesn’t depend on a functioning legal system or a credible sovereign guarantor. Gold doesn’t care if the Supreme Court overturns presidential dismissal precedents. It doesn’t care if the New START nuclear treaty expires without replacement, as it did in February. It exists outside the system, which is precisely why it appreciates when the system’s coherence is questioned.

The dollar, paradoxically, benefits from both scenarios in the short term. In an inflation crisis, the dollar weakens, but capital still flows to the U.S. because alternatives are worse—Europe is politically fragmented, China is opaque, and emerging markets lack depth. In an institutional crisis, the dollar strengthens because it’s the lingua franca of power. Even countries that resent American unilateralism need dollars to settle energy trades, service debt, and access global finance. The dollar’s role as the dominant reserve currency is less about economic merit than about network effects and coercive infrastructure. That gives it durability even in chaos—until the chaos is so extreme that the network itself fractures.

Silver’s message is simpler: if you’re buying precious metals as an economic growth play, you’re making a category error. The metal’s January rally was driven by narratives that assumed global growth would remain robust even as geopolitical risk premia rose. Those narratives have been stress-tested by reality. The Oracle layoffs—30,000 planned, according to reports—and the 25,000 tech job cuts in January alone suggest that corporate confidence is eroding. AI-driven productivity gains, rather than creating new economic activity, are being used to justify headcount reductions. In that environment, industrial silver demand contracts, and the metal’s price collapses back toward its commodity fundamentals rather than its monetary mythology.

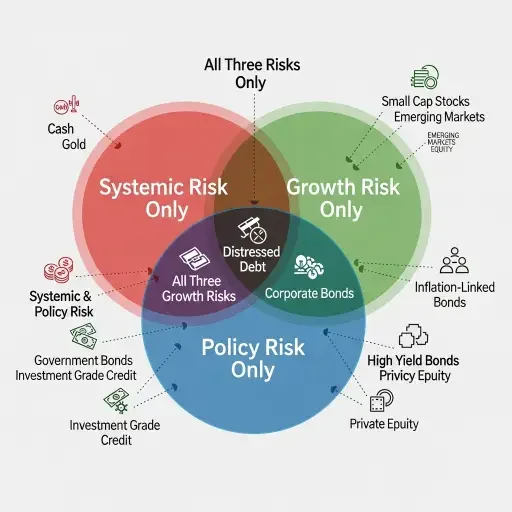

The deeper implication is that the safe haven taxonomy itself is breaking down. Investors are accustomed to a binary framework: risk-on (equities, high-yield credit, industrial commodities) versus risk-off (Treasuries, gold, the dollar). But February’s price action suggests a tripartite regime. There’s systemic risk (gold rallies, silver falls, the dollar strengthens), growth risk (silver and equities fall together, Treasuries rally), and policy risk (the dollar and gold both rally, Treasuries sell off on fiscal concerns). These regimes can overlap, creating correlation patterns that defy historical precedent. When the Fed is under political assault, Venezuela is under military occupation, and China is leveraging rare earth supply chains, all three regimes are active simultaneously.

The practical implication for portfolio construction is that diversification within safe havens is no longer sufficient. Holding gold and Treasuries together used to provide uncorrelated protection. Now, both can sell off if the binding constraint is fiscal—if markets decide that U.S. debt sustainability is the primary risk. Conversely, both can rally if institutional legitimacy is the threat. The correlation structure is unstable, which means hedges designed for one crisis mode can amplify losses in another.

The cleanest signal in the noise is gold’s relative strength versus silver. That spread—gold rallying while silver collapses—has historically marked the transition from growth concerns to systemic ones. In 2008, the same pattern emerged in the months before Lehman Brothers failed. In 2020, it appeared as COVID lockdowns transitioned from a growth shock to a monetary one. The divergence doesn’t predict the timing of a crisis, but it identifies the regime. Right now, the regime is one where investors are pricing institutional risk over cyclical risk. They’re not worried about whether the economy will grow next quarter. They’re worried about whether the frameworks that define ownership, currency, and sovereignty will remain legible.

Treasuries remain the deepest, most liquid safe asset, and that liquidity premium persists even when other fundamentals wobble. The dollar remains the reserve currency, but increasingly for coercive rather than cooperative reasons—a distinction that matters less for near-term price action than for long-term structural fragility. Gold remains the ultimate non-institutional asset, valuable precisely because it doesn’t require institutions to function. And silver remains what it’s always been: a commodity with monetary aspirations, useful in stable growth regimes and punished in unstable ones.

The whipsaw in metals isn’t a forecast. It’s a diagnostic. The market is telling us it no longer knows which risk to price, because the risks are simultaneous and contradictory. The traditional safe haven hierarchy—Treasuries for credit risk, gold for currency risk, the dollar for liquidity—assumes that only one risk dominates at a time. When all three are active, the hierarchy collapses. What’s left is a market that oscillates between fear modes rather than converging on a stable equilibrium. That’s not a metals story. It’s a regime story. And the regime is one where safety itself has become a contested concept.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Market data from CBS News, CNBC, Priority Gold; Federal Reserve policy statements; geopolitical analysis from Brookings Institution and Council on Foreign Relations; Treasury market data from Federal Reserve Board H.15 releases