Truist’s decision to downgrade Northrop Grumman is a focused interrogation of margins at a large prime contractor. The bank’s analysts pointed to rising input costs, program timing risk and the potential for increased subcontractor pass-throughs to erode operating margins. On the surface this is a single-stock reassessment; beneath it sits a signal to investors: margin assumptions that have supported defense multiples may be loosening.

That signal matters because defense equities trade not only on topline visibility—multi-year backlogs, long procurement cycles—but on predictability of cash margin. Historically, primes have carried premium valuations justified by sticky government demand and contract longevity. When a major analyst downgrades a prime for margin risk, the market is being asked to reassess the probability distribution of future free cash flow, not merely adjust for a serial one-off.

Two mechanisms connect Northrop’s problem to the wider complex. First, cost inflation: labor and subcontract pricing have risen across the supply chain. Second, program execution: schedule slips or technical slowdowns increase overhead and transition costs and can shift revenue mix toward lower-margin services or remediation work. If these pressures prove persistent and correlated across primes, multiple compression needn’t be dramatic to erase meaningful equity value.

Yet buffers remain. Government budgets are robust; the Pentagon’s multi-year commitments and the inertia of procurement cycles create a floor under revenue forecasts. For investors, the key distinction is between demand-driven risk and margin-driven risk. Demand risk (a cut in purchased systems) would be structural and severe. Margin risk, by contrast, is often transitory or contractually mitigable—change orders, cost-reimbursable provisions and renegotiations can restore economics over time.

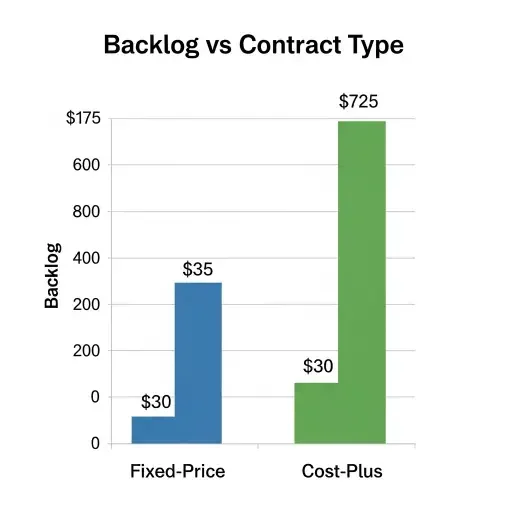

Parsing which it will be requires attention to three variables: backlog composition, contract type mix, and subcontractor health. Backlogs full of fixed-price awards are more exposed to cost overruns than cost-plus portfolios; service-heavy revenue may hide lower near-term margin volatility but portend longer-term margin erosion if labor costs rise. Subcontractor stress matters because primes absorb or are forced to arbitrate overruns; a chained stress event among specialized suppliers amplifies margin pressure rapidly.

The market’s reaction so far has been measured. Northrop’s stock traded down after the note, but the decline was a revaluation rather than a rout—investors appear to be discriminating between headline risk and systemic contagion. That discrimination is rational: primes have diversified portfolios, multiple revenue streams across defense and space, and substantial backlog that reduces immediate cashflow surprise.

A modest repricing across the sector would follow a realistic path: selective compression of multiples at firms with larger fixed-price exposure, downward revision of forward margins in models, and tighter scrutiny on bids with thin contingency assumptions. In practice, that looks like a few percentage points trimmed from EV/EBITDA or P/E ratios rather than a wholesale de-rating. For long-only investors the calculus is simple: are balance sheets and backlog depth sufficient to weather a temporary margin trough?

Active managers, however, will have more nuanced choices. They can underweight or hedge contractors with concentrated program risk and heavy fixed-price exposure, while selectively adding to names where backlog, classified programs and higher-margin services insulate cash conversion. Private equity and credit markets will also watch: sustained margin pressure can convert covenant-friendly liquidity into refinancing risk for suppliers, tightening the ecosystem in ways that ultimately leak to primes.

There are also strategic implications beyond near-term earnings. Persistent margin pressure could accelerate two structural responses. One, manufacturers will push harder to move work off the balance sheet—outsourcing, partnerships, and higher use of cost-plus subcontracting. Two, primes may accelerate technology-driven efficiency efforts—digital engineering, additive manufacturing and supply-chain analytics—to cut cycle time and reduce rework. Both responses have lagged benefits and require upfront investment, which paradoxically can depress short-term margins further.

For investors focused on actionables: first, stress-test models for a 100–200 basis point margin hit across the next two fiscal years. Second, map contract mix in public filings—identify fixed-price heavy programs and quantify potential rollback in margin contribution. Third, monitor supplier credit and purchasing manager data for signs of cascading cost pressure; a spike in subcontractor defaults or delayed deliveries is a much noisier but reliable early warning.

The balance of probabilities today favors a measured repricing rather than a systemic collapse. Demand fundamentals—geopolitical tensions, defense modernization, and budget authorizations—remain supportive. But the downgrade is a timely reminder that the margin calculus which has underwritten defense multiples is not immutable. Small shifts in cost structure or program execution can compress realized free cash flow more quickly than headline revenue data implies.

If Truist is correct that Northrop’s margins will narrow meaningfully, the market’s work is straightforward: reprice those future cash flows and tilt portfolios accordingly. The more important test, for both managers and allocators, will be whether margin pressure is idiosyncratic to complex integration problems at one prime, or a correlated phenomenon rolling through suppliers and programs. In the latter case, the downgrade will prove to be the opening bell of a modest, selective sector repricing; in the former, a single cautionary note in an otherwise steady chorus.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Analysis based on Truist downgrade note, Northrop Grumman financials, industry backlog data, and defense contracting cost trends.