Every energy transition has its bargain: cheaper electrons for less reliability, or cleaner power for higher cost. The new bargain states are writing is different. Policymakers increasingly treat nuclear — in particular small modular reactors (SMRs) — not as a distant technological moonshot but as the only mature technology that delivers firm, carbon-free, 24/7 power. The implication is blunt: when the stakes are decarbonization plus grid stability, capital follows rules that guarantee predictable returns. That contextual pivot is what’s turning propaganda into projects.

Start with the binding constraints. Utility companies answer to markets and regulators. Investors answer to returns and risk mitigation. States answer to emissions targets and the political pain of blackouts. Which of these actors, if they changed course, would force the rest to adapt? Increasingly the answer is capital. Federal tax credits, state-backed power purchase agreements, and regulated cost-recovery mechanisms are making SMRs financeable. Once investment moves, utility integrated resource plans (IRPs) and transmission planning must follow.

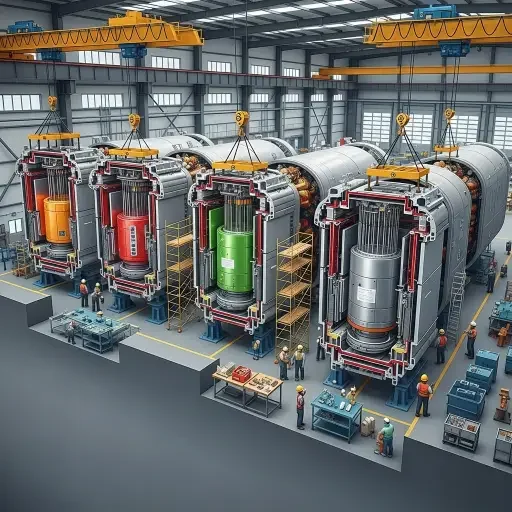

SMRs’ appeal is compact and contractual. Unlike gigawatt-scale reactors that require decade-long site construction and political patience, SMRs promise factory-built modules, shorter on-site schedules, and scalability by adding units. For grid planners, the central value is dispatchability: a guaranteed supply during calm-solar nights and wind lulls. For regulators, it’s predictability: known capital costs recovered through rate mechanisms rather than volatile gas markets.

The policy suite enabling this shift is explicit and targeted. States are offering long-term offtake contracts, loan-loss reserves, and streamlined siting rules that shrink the point-of-entry risk for financiers. Some states have addended IRP guidance to value capacity attributes differently — explicitly crediting carbon-free dispatchability in planning models. Those adjustments matter: a resource that clears as a capacity product can justify large upfront capital because its revenue stream is contractable and predictable.

Capital is responding in two visible ways. First, regulated utilities are reallocating portfolios: longer-lived, lower-variable-cost assets (like SMRs) are displacing short-lived peakers and merchant gas contracts in planning scenarios. Second, private capital is syndicating around state-supported projects where contract structures mimic muni bonds or rate-based returns. The message is practical: SMRs become investable when their risk profile resembles infrastructure, not speculative tech.

This reallocation has systemic effects. On one axis it changes marginal investment — utilities will defer new combined-cycle gas plants if an SMR’s levelized cost of energy (LCOE) plus capacity payments looks comparable on a forward-looking basis. On another axis it alters grid operations: operators must integrate slow-to-ramp baseload with fast-flexible resources (storage, demand response, and peaking gas) to maintain reliability and economic efficiency. That coupling raises questions about market design: how should capacity markets and energy markets price firm, carbon-free flexibility?

Risk remains nontrivial. Cost overruns, supply-chain bottlenecks for specialized components, and regulatory delays can still derail economics. SMRs are not a magic bullet against political risk — witness the uneven progress across states with different permitting regimes. Yet modern policy tools blunt these risks: milestone-based grants, modular factory scaling, and federal loan guarantees can compress tail-risk into tractable, insurable tranches.

Investors are particularly sensitive to one new accounting fact: when a state endorses an SMR with a rate-recovery or long-term PPA, the project’s cash flows become quasi-sovereign. That makes credit enhancements cheaper and unlocks institutional capital that historically avoided merchant power but embraces regulated returns. The corollary is important — it concentrates power in the hands of those who underwrite: if capital prefers SMR-backed returns, it will steer utilities toward projects that preserve those revenue characteristics.

This capital steering produces political ripple effects. Labor unions, siting opponents, and incumbent gas suppliers all become stakeholders in a new negotiation. States that champion SMRs must reconcile community-level concerns with the macro calculus of climate risk. The technical allure of SMRs — smaller footprints, passive safety systems, incremental deployment — helps, but the social license still requires transparent cost allocation and workforce development commitments.

The practical takeaway for investors and utilities is clear and actionable. First, model policy contingencies as primary inputs, not afterthoughts; shifts in IRP valuation rules materially change project NPV. Second, stress-test portfolios for mixed-operation regimes: high baseload nuclear plus high-flex renewables implies different reserve margins and ancillary service markets. Third, price political and siting risk separately, and look for structures that convert policy support into tradable credit enhancements.

In an energy system racing to decarbonize, states are no longer passive arbiters; they are active capital allocators. By treating SMRs as bankable firm capacity, they reroute flows of investment from short-horizon merchant bets into long-dated infrastructure. The near-term consequence is a palpable reordering of utility capital plans; the longer-term question is whether those investments accelerate deep decarbonization or simply lock in a new set of incumbencies.

Concluding checksum: SMRs matter because they translate the abstract goal of zero-carbon grids into contractable, investable assets. The rule for decision-makers is straightforward: if you want 24/7 carbon-free electricity to be real, you must make its cash flows real first.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

State energy policy documents and utility commission filings; SMR technology vendor announcements and project proposals; nuclear industry analysis from trade publications and energy research firms; utility capital planning documents.