SoftBank paid roughly $3 billion in cash for DigitalBridge. That sentence compresses the deal into a tidy fact; it understates the directional arrow it stakes across the AI economy. This is not an acquisition for adjacency or financial engineering. It is a posture—capital claiming the physical substrate of computation: land, power contracts, fiber, and the contractual plumbing that keeps GPUs humming at scale.

Why does that matter? Because the current geography of AI profitability is shifting. For the past decade the conversation centered on algorithms, chips and cloud marketplaces. Today, rising demand for larger models and real‑time workloads has moved binding constraints off the GPU floorplate and onto anything that can deliver sustained power density, predictable latency, and colocated networking. Those constraints are physical and local—and capital can buy them.

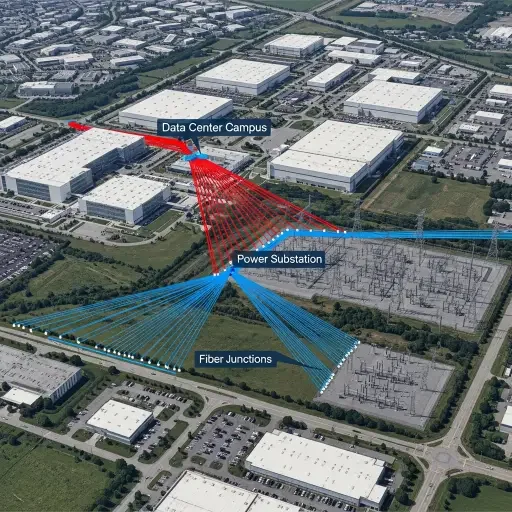

SoftBank is not buying racks; it is buying constraints. DigitalBridge owns a portfolio of data centers, long‑dated leases and embedded customer relationships—things that look like boring balance‑sheet items until you realize AI consumes electricity the way Netflix consumes content: relentlessly and at scale. Power purchase agreements, real estate positions near fiber hubs, and operational expertise are the throttles on how much compute can run where. Owning those throttles means owning leverage.

SoftBank’s history makes the move legible. Masayoshi Son’s portfolio has oscillated between visionary hits and headline-making losses; his frame for scale is persistent: concentrate assets that can compound across cycles. Buying DigitalBridge with cash compresses execution risk and signals a long horizon—SoftBank prefers owning the land over renting the software layer when the returns appear resiliently sticky.

Concretely, this purchase does three things for SoftBank. First, it positions the firm as a wholesale landlord to the AI economy—an owner of scarcity (power capacity, interconnect points, colocation footprints). Second, it creates optionality: SoftBank can monetize through leases, joint ventures, or vertical integration with chip and cooling partners. Third, it shields returns from the margin squeeze in cloud commoditization; as compute scales, differentiation will increasingly be derived from where and how workloads are hosted.

Specifically: AI workloads are power‑hungry and latency‑sensitive. DigitalBridge’s assets sit near transmission nodes and fiber crossroads; many come with long‑term utility contracts and a client base already paying for guaranteed uptime. Those features are the equivalent of toll booths on data flows—small friction for customers, large rents for landlords.

The market reaction will be instructive. Investors have paid premiums before for hyperscale real estate—think of the REITs and colo providers that re-rated as cloud demand surged. But this deal is different because it’s not public markets repricing; it is a concentrated capital allocation by a single actor. That matters for two reasons. One, private control reduces the speed of market correction: SoftBank can hold, refit and integrate without quarterly scrutiny. Two, concentration creates optionality to re‑compose the value chain: SoftBank could pair data‑center capacity with exclusive supply arrangements for chips, cooling hardware or even bespoke AI services.

This is where Platform and Capital intersect. Platform in the technical sense—networks, racks, and cooling—sets the architectural constraints. Capital decides who owns those constraints. SoftBank choosing ownership signals a belief that ownership of infrastructure will be a superior vector for capture than attempting to invest upstream (models) or downstream (applications).

An investor reading the deal sees three risk vectors. Operational risk: data centers are management‑intensive; margins depend on uptime, efficient thermal design and negotiating utility rates. Regulatory risk: local permitting, grid constraints and environmental rules can delay expansion or add costs. Market risk: if model architectures pivot to edge‑distributed compute or more efficient parameterizations, demand patterns could change. Each risk, however, is addressable with capital—upgrading cooling, securing new PPAs, or reshaping tenant mixes.

The counterargument is simple and moral: betting on physical infrastructure is a slower, plodding game compared to the glories of a breakthrough model. But slower does not mean lesser. The neural economy requires steady rails—repeatable megawatts, predictable networking, and safe facilities—before speculative innovation can reliably scale. In that sense, the deal reads as pragmatic insurance: place capital where failure to deliver would choke the entire stack.

SoftBank’s cash purchase of DigitalBridge is a claim on physical scarcity. If chips are the CPUs of an emerging economy, data centers are its ports and power plants—the logistical chokepoints through which value must flow. When an industry is bounded by physical constraints, the capital allocators who own those constraints command outsized optionality.

For practitioners and investors: watch the integration play. Does SoftBank rebrand, vertically integrate with equipment suppliers, or keep DigitalBridge as an agnostic landlord? Each choice signals a different thesis about where margins will reside. For the broader AI ecosystem, the message is clearer: the quiet infrastructure beneath the models is becoming an explicit battleground—and capital has just staked its flag.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

SoftBank and DigitalBridge company announcements and acquisition disclosures; data center industry analysis from industry research firms; AI infrastructure market reports; real estate and power contract market data.