Thanksgiving 2025 arrives with an unwelcome side dish: a nearly 10% increase in dinner costs that functions less as seasonal inflation and more as a diagnostic scan of America's food infrastructure. Recent analysis shows the full meal climbed 9.8% from last year—triple the overall inflation rate—but the aggregate number obscures what really matters. The story lives in the extremes: onions surging 56%, spiral hams jumping 49%, cranberry sauce climbing 22%. These aren't random price movements. They're symptoms of a supply system operating at its fracture points.

The conventional narrative focuses on turkey—down 16% this year, a seeming win for consumers. But this misses the architecture of what's breaking. The sides, those supposedly mundane ingredients that transform a meal from protein delivery to cultural ritual, reveal the true stress fractures. When the supporting elements cost significantly more while the centerpiece gets cheaper, you're watching a system fragment in real time.

The Onion Paradox: How Water Became Pricing

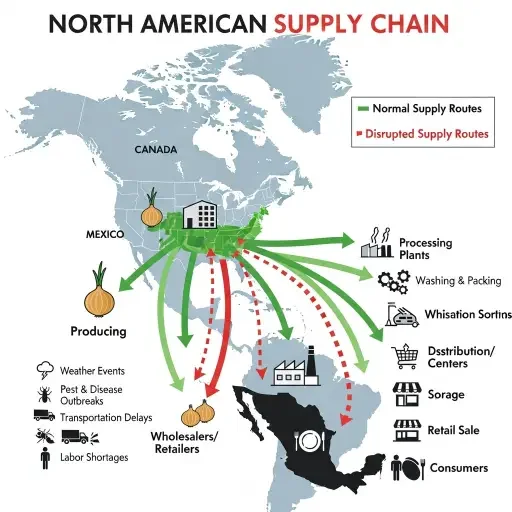

Consider the onion, that humble allium experiencing a 56% price explosion. The spike traces back to an interconnected failure cascade that began in 2024. Water shortages in Mexico and Texas during planting season created supply constraints, but that's only the ignition point. What followed demonstrates how modern food systems amplify rather than absorb shocks.

Mexican onion harvests were delayed until mid-February, pushing the U.S. to supply Mexico's domestic needs—exactly backward from normal trade flows. This reversal didn't just tighten American supplies; it revealed the brittleness of cross-border agricultural interdependence. When climate stress hits one production region, the entire North American onion economy inverts. White onion prices rocketed above $50 per 50-pound sack in 2024, compared to $8-10 in March 2023 when Mexican shipments ran on schedule.

The onion crisis exposes something larger: agricultural supply chains built on just-in-time principles that assume stable weather patterns. That assumption no longer holds. Unpredictable weather conditions including droughts, excessive rainfall, and temperature fluctuations have made consistent, high-quality crop production increasingly difficult. The system has no slack, no buffer zone. When precipitation patterns shift or temperatures spike, prices don't merely adjust—they detonate.

The Ham Anomaly: When Disease Meets Policy

While onions reveal climate vulnerability, the 49% spiral ham price increase tells a different story—one where biological and political forces collide. The narrative starts with avian flu, which has affected 1,431 poultry flocks across all 50 states and Puerto Rico since 2022, impacting an estimated 138.7 million birds. But here's the peculiar part: consumers substituting away from poultry should have increased pork demand gradually. Instead, ham prices spiked dramatically.

The explanation requires looking at second-order effects. The U.S. turkey flock dropped to its lowest size in nearly 40 years, with wholesale turkey prices surging 75% since October 2024. This drove consumers toward alternative proteins—beef roasts up 20%, ham climbing alongside. But demand surge alone doesn't fully explain a 49% increase. The missing piece: Trump's 50% tariff on steel drove up canning costs for approximately 80% of canned goods that rely on imported steel.

Steel tariffs might seem disconnected from fresh meat pricing, but they're not. Industrial food processing depends on steel for equipment, transportation, and packaging across the supply chain. When steel costs spike, the entire apparatus of getting protein from farm to grocery cooler becomes more expensive. Ford Motor Company reported that tariffs added $500 to $1,000 to each vehicle's cost—and similar cost multipliers hit every industry touching steel, including food distribution.

The ham price surge, then, emerges from a perfect storm: avian flu reducing turkey supply, driving protein substitution toward pork and beef, while tariff policies simultaneously raise the infrastructure costs of moving that meat through processing and distribution networks. It's not one thing breaking. It's everything breaking at once, in ways that compound rather than cancel out.

Canned Goods as Canary: The Tariff Tax Nobody Discusses

The turkey and ham get attention, but look at what's happening to shelf-stable products. Canned fruits and vegetables across the board are up 5% year-over-year, with creamed corn jumping 22%. This isn't about fresh produce availability or weather disruptions. This is pure policy impact translated into grocery prices.

The doubling of U.S. tariffs on imported steel led to a projected increase of up to 30 cents per can for canned food products. When roughly four-fifths of canning operations depend on imported steel, and domestic steel manufacturers raise prices in tandem, there's nowhere to escape the cost increase. The canned goods aisle becomes a real-time demonstration of how trade policy cascades through supply chains.

What makes this particularly revealing is the disconnect between rhetoric and reality. Political discourse frames tariffs as protecting domestic industry, but even domestic steel manufacturers raised prices under the cover of tariffs, creating a price ceiling effect where everyone adjusts upward regardless of their actual cost structure. The consumer pays, the food processor pays, but the purported beneficiary—domestic steel production—simply captures rent rather than expanding capacity.

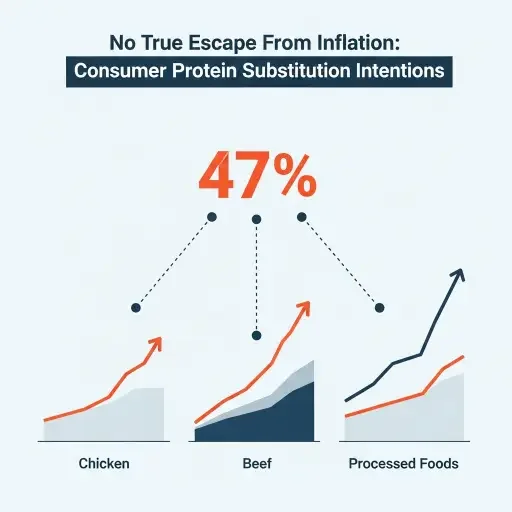

The Substitution Trap: When Alternatives Also Inflate

Economic theory suggests consumers should substitute away from expensive items toward cheaper alternatives. Research reveals 47% of Americans are trading turkey for cheaper alternatives, with 38% swapping for chicken and a third opting for burgers, pizza, or fast food. But here's where theory meets reality's complexity: the alternatives are also experiencing their own supply shocks.

Chicken prices, theoretically insulated from turkey-specific avian flu, have been affected by the same disease vectors. More than 157 million chickens have been affected by avian influenza since January 2024. The virus doesn't respect species boundaries cleanly, and biosecurity measures that protect chickens also add costs. When consumers flee turkey toward chicken, they're not actually escaping the underlying supply chain stress—they're just encountering it in a different form.

The substitution trap extends beyond protein. Potatoes saw the biggest price hike at 3.7% year-over-year, affecting sides that families might choose as budget-friendly options. Even storage becomes more expensive—heavy-duty aluminum foil prices climbed 40% due to those same steel and aluminum tariffs. The economics of thrift become more expensive, a kind of inflation that punishes the very adaptations designed to avoid it.

The Regional Fracture: Why Geography Now Determines Food Costs

National price averages mask dramatic regional variations that reveal infrastructure disparities. The classic Thanksgiving meal costs most in the West at $61.75, compared to $50.01 in the South—a 23% difference for the identical menu. These aren't trivial variations. They indicate that food distribution networks function at wildly different efficiency levels depending on location.

The expanded meal with ham, potatoes, and green beans cost $84.97 in the West versus $71.20 in the South, amplifying the regional gap. Why? Part of the answer involves California's Sustainable Groundwater Management Act going into effect in 2025, which creates corresponding cost impacts on growers that vary by district and water availability. When water costs more to access legally, agriculture becomes more expensive, and those costs propagate through regional supply chains.

But water policy alone doesn't explain 20-25% price differentials. The deeper issue involves logistics infrastructure. Western distribution networks depend more heavily on long-haul transportation, which makes them more sensitive to fuel costs and tariff-induced equipment price increases. When Walmart reported a 5% rise in logistics costs due to longer shipping routes in their supply chain diversification efforts, that pattern scales across Western food distribution generally.

The Climate Variable: Destabilization as the New Normal

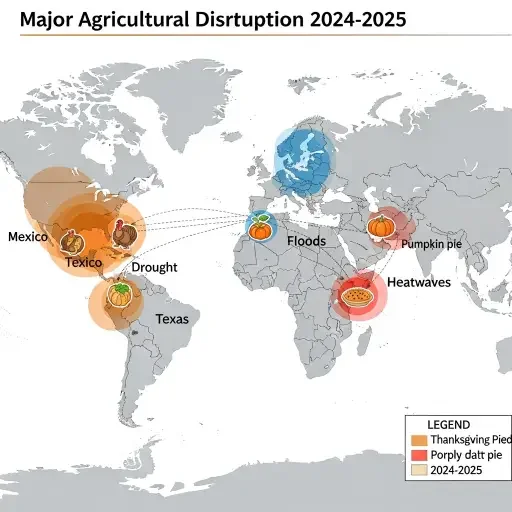

Thread through all these price spikes runs a common element: weather pattern disruption. Italy's 2024/25 onion harvest faced repeated rains and high humidity, disrupting harvest and creating quality issues that lead to high waste levels. Droughts, excessive rainfall, and temperature fluctuations are making it harder for farmers to grow consistent, high-quality crops across multiple growing regions simultaneously.

This isn't an anomaly to weather through. Climate pattern destabilization transforms the fundamental economics of agriculture. Food systems designed around predictable growing seasons, consistent precipitation, and stable temperature ranges now operate in an environment where those assumptions fail regularly. In India, heatwaves in summer 2024 resulted in massive crop damage causing significant shortage in onion powder markets—a pattern that ripples through global food processing.

The response can't simply be "build more resilient supply chains." When weather becomes fundamentally less predictable, the concept of resilience itself needs redefinition. Traditional approaches involved diversifying suppliers geographically—but if climate disruption affects multiple regions simultaneously, diversification provides less protection. The 2024 onion crisis demonstrated this precisely: Canada and New York had short crops due to torrential rains during late summer harvest, while Mexico faced water shortages—different climate problems, same outcome.

The Policy Layer: How Tariffs Amplify Natural Shocks

If climate creates the underlying instability, policy decisions determine whether that instability gets amplified or absorbed. The 2025 Thanksgiving price structure suggests amplification won decisively. Trump's 50% steel tariff drove up costs throughout canned goods production, transforming what might have been modest price adjustments into sharp spikes.

The timing matters immensely. Industries anticipated tariffs and preordered materials in Q4 2024, creating short-term inventory buffers—but those buffers run out. By Thanksgiving 2025, the stored inventory from pre-tariff purchasing has been depleted, and current prices reflect the new cost structure. This explains why some retailers could offer temporary deals even as underlying costs climbed: they were selling down inventory purchased before tariff implementation.

Years of persistent inflation and supply chain disruptions have already driven up cost structures for the food industry, with production costs having doubled from pre-pandemic figures. Layering tariffs onto an already-stressed system doesn't just add percentage points—it can trigger nonlinear responses where systems tip from manageable stress to breakdown.

The Labor Thread: Invisible but Essential

Running through every supply chain element, largely invisible in price discussions, is labor availability. Many agricultural sectors are experiencing labor shortages impacting the planting, tending, and harvesting of crops—a problem that compounds weather disruptions. When climate makes farming more difficult and unpredictable, the work becomes less attractive. When labor becomes scarce, crops that require intensive hand labor (like onions) become more expensive to produce.

The largest increases in Thanksgiving dinner costs came from processed products, with dinner rolls and cubed stuffing both increasing over 8% from 2023, driven by non-food inflation and labor shortages across the food supply chain. Processing facilities, trucking operations, warehouse logistics—every node in the supply chain competes for workers in a tight labor market, driving up wages and, consequently, food prices.

This isn't simply about finding more workers. The deeper issue involves attractiveness of agricultural and food processing work. When Perdue Farms announced layoffs of nearly 300 employees at an Indiana turkey plant in September, reportedly due to bird flu and consumer shifts toward other meats, it demonstrated how supply chain instability creates employment instability, which makes it harder to maintain the workforce needed when production does recover.

The Consumer Response: Behavior Under Pressure

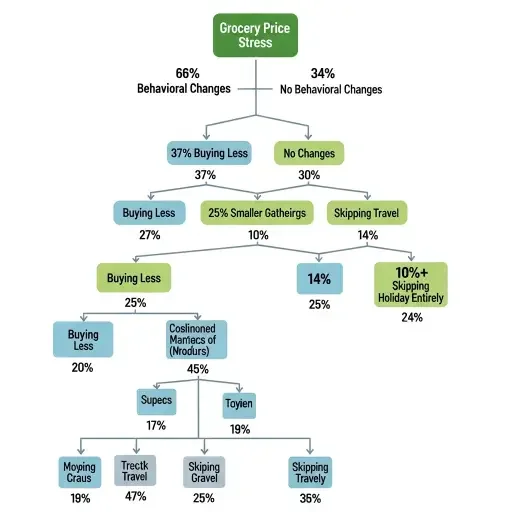

Nearly two-thirds of people report stress about Thanksgiving prices, with 37% planning to buy fewer items and one-quarter planning smaller gatherings. This isn't mere economic adjustment—it's the social fabric of American holidays reshaping under financial pressure. When 14% skip traditional travel and more than one in ten skip the holiday entirely, food prices have moved beyond economics into cultural territory.

Research shows 57% of Americans say they're being "priced out" of their own kitchen, with groceries too expensive to cook at home for the holiday. The substitution patterns reveal something unsettling: A third of consumers say they'll opt for burgers, pizza, or fast food to keep costs down rather than preparing traditional meals. When the economics of home cooking become prohibitive, you're watching food system dysfunction manifest in changed social practices.

Retailers recognize the pressure. Aldi offered its lowest-priced Thanksgiving package in years at less than $4 per person to serve 10 people, while Walmart reduced its deal from 29 items in 2024 to 23 items in 2025 to maintain low headline prices. These tactics acknowledge consumer stress but also reveal the limits of retail intervention—stores can offer deals, but they can't fundamentally overcome supply chain cost increases without absorbing unsustainable losses.

What Thanksgiving Prices Predict

The 2025 Thanksgiving table functions as an economic leading indicator. The specific price movements reveal which systems are under greatest stress: climate-sensitive agriculture (onions, fresh produce), disease-vulnerable animal agriculture (poultry, eggs), tariff-sensitive processed goods (canned items), and labor-intensive products (baked goods, prepared items). These aren't independent problems—they're interconnected vulnerabilities in a system operating with minimal redundancy.

Even though the price tag for this year's Thanksgiving meal is down 5% overall, it's still up nearly 20% from just five years ago. The longer trend matters more than year-over-year fluctuations. Food prices have reset at a higher baseline, and the structural factors driving that reset—climate instability, supply chain fragility, policy interventions—show no signs of resolving. Consumers are exhausted from years of inflation, and it will take more than the past two years' improvements to ease the pain.

The question isn't whether next year's Thanksgiving will cost more or less. The question is whether American food systems can adapt to operating in a permanently higher-volatility environment. Can agriculture adjust to unreliable weather? Can supply chains build in the redundancy necessary to absorb shocks? Can policy create stability rather than amplification? The onions and hams suggest the answer remains uncomfortably uncertain.

Perhaps most tellingly, the average American has to work 9% less time to pay for this year's Thanksgiving dinner compared to 2023, because average wages rose 4%—but that calculation assumes stable employment in sectors increasingly affected by the very supply chain disruptions driving food prices. When poultry producers lay off workers due to avian flu, when agricultural employment becomes less stable due to climate shocks, wage growth provides less protection than it appears.

The broken supply chains revealed at Thanksgiving 2025 aren't anomalies waiting to be fixed. They're the visible surface of systemic adaptations struggling to happen fast enough. Every price spike represents a system trying to signal scarcity, trying to redirect resources, trying to adapt—but doing so through mechanisms that distribute pain unevenly and unpredictably. The real cost isn't measured in the dollars spent on onions or ham. It's measured in the growing brittleness of the networks that connect American farms to American tables, and the narrowing margin between routine and crisis in feeding a nation.

Sources

Analysis based on data from Groundwork Collaborative, The Century Foundation, American Farm Bureau Federation, USDA market reports, and multiple supply chain industry sources