The vacuum cleaner that learned to navigate around furniture has now run out of runway entirely. On December 14, 2024, iRobot filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, ending a 35-year run that transformed home robotics from science fiction into a commodity appliance. The company will be acquired by Shenzhen Picea Robotics—not coincidentally, the same Chinese firm that manufactures its products and holds most of its debt.

There is a certain irony here, sharp enough to draw blood. iRobot invented the category. Since launching the Roomba in 2002, it sold more than 50 million robots worldwide. The brand became synonymous with robotic vacuums, spawning memes, cat videos, and even a verb form of home automation. Yet by 2024, Chinese rivals such as Ecovacs Robotics had eroded margins with cheaper alternatives offering competitive features. The pioneer found itself outmaneuvered by fast followers operating with structural advantages it could not match.

The Amazon Deal That Wasn't

The story pivots on a transaction that never closed. In 2022, Amazon agreed to acquire iRobot for $1.7 billion—what would have been the retail giant’s fourth-largest acquisition at the time. For a cash-burning robotics company facing intensifying competition, this represented salvation through scale. Amazon’s distribution network, manufacturing leverage, and patient capital could have repositioned iRobot against the Chinese manufacturing juggernaut.

European regulators blocked the deal in January 2024, citing concerns that Amazon could restrict marketplace access for competing robot vacuum makers. The rationale—protecting competition—proved grimly ironic. iRobot’s CEO, Colin Angle, resigned; the company cut 31% of its workforce; and shares collapsed. What followed was a slow-motion failure, each earnings report documenting accelerating decline.

The Carlyle Group had extended a $200 million bridge loan in 2023, assuming the Amazon deal would close. When regulators killed the acquisition, Amazon paid a $94 million breakup fee—a fraction of the strategic value the merger would have delivered. The remaining cash cushion evaporated quickly. By November 2024, iRobot owed Picea Robotics $161.5 million for manufacturing services, with $90.9 million past due. The manufacturer had become the creditor; the creditor would become the owner.

The Manufacturing Trap

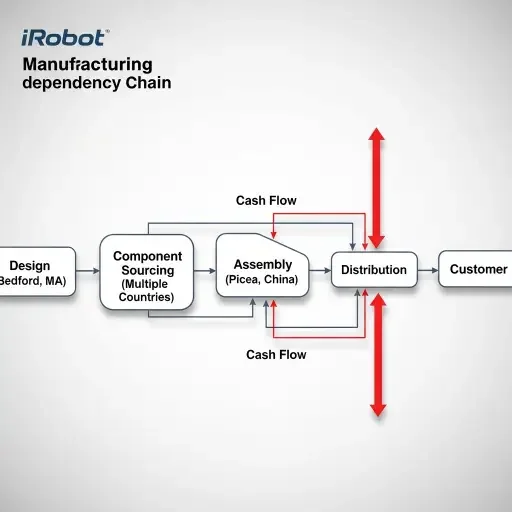

This progression—from customer to debtor to acquisition target—reveals the structural vulnerability that doomed iRobot. Like many Western hardware companies, iRobot outsourced manufacturing to minimize capital intensity and preserve flexibility. That strategy worked when the company controlled its destiny. It became a trap once financial stress emerged.

Roborock, a Beijing-based competitor founded in 2014, can bring products to market in roughly six months—compared to iRobot’s nearly two-year development cycle. The velocity advantage stems from China’s integrated supply-chain ecosystem. As Roborock’s president explained, China’s manufacturing environment makes “design and production very easy, competent, and efficient.” Components, tooling, assembly, and testing sit in close physical proximity—often within the same province.

The cost differential compounds the speed advantage. Industry analysts estimate that Chinese robots achieve roughly 80% of the performance of premium Western competitors at about 30% lower cost. For many consumers, particularly in price-sensitive markets, this is an acceptable trade-off. iRobot was forced to compete simultaneously on quality and price against firms with inherent advantages on both fronts.

The Capital Structure Mismatch

Between January and December 2024, iRobot reduced its workforce by more than 50%, cutting headcount to 541 employees. The restructuring hit its cost targets, but revenue collapsed faster. Fourth-quarter 2024 revenue fell 47% in the United States, 34% in Japan, and 44% in Europe year over year. Cost discipline could not outrun market share erosion.

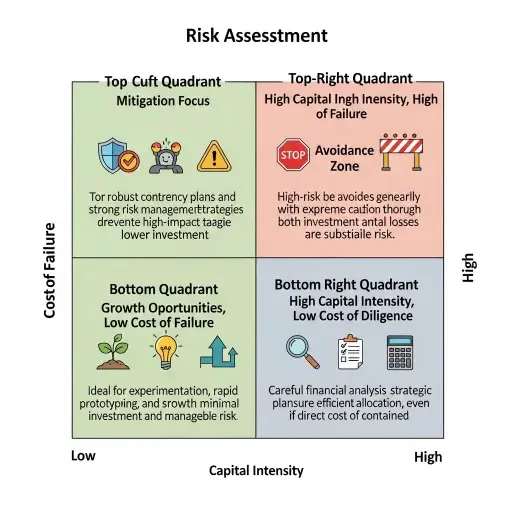

This exposes a central challenge in robotics financing: the mismatch between capital requirements and investor timelines. Robotics demands patient capital—funds willing to absorb years of losses while products mature and manufacturing scales. Traditional venture capital has long avoided hardware for this reason. Even with renewed interest driven by AI, robotics still accounts for roughly 10% of venture capital technology investment.

Chinese competitors operate under different constraints. Government subsidies allow sustained R&D investment while reducing unit costs. Programs such as Made in China 2025 explicitly prioritize robotics as a strategic sector. This state-backed patience allows firms to endure losses longer while building market dominance.

iRobot, by contrast, was exposed to public-market quarterly pressures. Valued at $3.56 billion in 2021 during pandemic-driven demand, its market capitalization collapsed to roughly $140 million by late 2024. Operational excellence alone could not overcome the structural capital disadvantage.

What Other Robotics Companies Must Learn

The lessons from iRobot’s collapse divide into strategic imperatives and structural realities.

Manufacturing control matters. Outsourcing core production—especially to suppliers operating in competitive markets—creates existential dependency under stress. Under the bankruptcy plan, Picea will take 100% of iRobot’s equity while canceling approximately $190 million in debt and $74 million in manufacturing obligations. The manufacturer acquired the company for the cost of unpaid invoices.

Regulatory risk shapes exit paths. European Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager blocked the Amazon–iRobot deal despite acknowledging Amazon does not compete directly in robot vacuums. The decision prioritized hypothetical competition concerns over the practical consequence: leaving iRobot unable to compete against Chinese manufacturers.

Product velocity now defines advantage. Chinese robotics firms iterate dramatically faster due to supply-chain density and domestic competition. Western firms must either match that velocity—often requiring proximity to Asian manufacturing hubs—or differentiate through brand, services, enterprise relationships, or regulatory complexity.

Capital structure must match timelines. Robotics companies face a paradox: scale is required to raise capital, but capital is required to reach scale. Some firms now experiment with Regulation A+ offerings, raising up to $75 million annually from public investors to secure more patient funding.

Know when innovation gives way to execution. iRobot thrived when technological barriers were high. By 2024, robotic vacuums had commoditized. Once this transition occurs, success depends less on R&D and more on manufacturing efficiency and cost structure—domains where Chinese firms possess durable advantages.

The Broader Reconfiguration

iRobot’s bankruptcy marks more than a single failure; it reflects a global reordering of robotics. China now accounts for roughly 52% of industrial robot installations and files nearly three times as many robotics patents as the United States. Innovation leadership has fragmented geographically.

This mirrors earlier shifts in consumer electronics, solar panels, and EV batteries—industries pioneered in the West but scaled in Asia. Structural factors—labor costs, supply-chain density, industrial policy, and capital availability—shape outcomes more than individual execution.

Western robotics companies must define defensible positions. Some may pursue vertical integration and premium branding. Others may focus on regulated or specialized niches. Still others may partner on manufacturing while retaining control over IP and customer relationships.

The path iRobot did not take—building domestic manufacturing with patient capital—may have been prohibitively expensive. Or it may have preserved independence. What is clear is that the path it did take—outsourced manufacturing combined with public-market pressure—proved fatal once competition intensified and capital vanished.

The Roomba will continue operating in millions of homes. Even if iRobot’s cloud services eventually shut down, the machines will keep cleaning—reverting to their essential function. The technology survives, even as its creator disappears into the manufacturing infrastructure that ultimately consumed it.

Sources

TechCrunch, Reuters, CNBC, Bloomberg, ITIF robotics analysis, Fortune, venture capital research