Every great platform eventually becomes a prison. NVIDIA built the deepest moat in computing history with CUDA—17 years of accumulated expertise, millions of lines of optimized code, an entire generation of developers who think in its paradigms. But paradigms shift. And when they do, yesterday's fortress becomes tomorrow's constraint.

The Gravity Well Problem

CUDA launched in 2006 to solve the GeForce 8800 GTX's problems: offloading embarrassingly parallel workloads from CPUs, managing explicit memory transfers between host and device, programming at the kernel level. These were elegant solutions for their moment. Seventeen years later, they're archaeological artifacts masquerading as modern infrastructure.

Consider what 2025's AI workloads actually need. Heterogeneous computing across vision, language, and robotics. Massive parallelism that transcends GPU boundaries through distributed training and mixture-of-experts routing. Dynamic compute graphs that current CUDA handles with the grace of a mainframe processing web traffic. Memory hierarchies spanning HBM, DRAM, SSDs, and network-attached storage—seamlessly, not through explicit cudaMemcpy calls that read like COBOL.

NVIDIA's engineers are brilliant. They've optimized CUDA relentlessly. But every optimization is incremental refinement of a 2006 paradigm. They cannot break backward compatibility with millions of lines of legacy code. They cannot rethink the fundamental model without triggering customer panic. They're trapped by their own success—maintaining a platform designed for problems that no longer exist while trying to serve problems it was never meant to solve.

The Kernel Abstraction Is Wrong

The deeper issue isn't just age—it's architectural mismatch. CUDA's kernel abstraction made sense when GPUs were coprocessors for scientific computing. Today's large language models need pipeline parallelism, tensor parallelism, sequence parallelism orchestrated across thousands of accelerators. The current approach? Hack it together with NCCL and manual orchestration. What's needed? Native distributed primitives that treat 10,000 GPUs as one coherent compute fabric.

Flash Attention exists because CUDA's memory hierarchy abstractions are fundamentally wrong. The fact that we need custom kernels for attention—the most common operation in modern AI—reveals that the primitives are broken. TensorRT optimizations require expert knowledge. Kernel fusion decisions are manual. Performance portability is a cruel joke; every new architecture demands new hand-tuned kernels from specialists who spent years learning CUDA's idiosyncrasies.

This isn't an accident of implementation. It's the inevitable consequence of building 2025's requirements on 2006's foundations.

LLMs Will Write Better Kernels Than Humans

Here's where the phase transition becomes visible: Large language models already write competitive code. Not in some distant future—now. AlphaCode produces programming solutions at human-competitive levels. Current LLMs optimize CUDA kernels with proper prompting. Give an LLM hardware specifications, a computation graph, and profiling data, and it will search optimization spaces that human experts never explore because the combinatorial explosion is too vast.

What this enables is explosive. A competitor doesn't need 17 years of accumulated CUDA tribal knowledge. They need three components: a clean hardware abstraction layer (something like MLIR, or better), an LLM-powered compiler that converts high-level compute graphs into optimal kernels for any architecture, and auto-adaptation that generates optimized code when new hardware drops—in hours, not years.

The implications cascade rapidly. New GPU architecture launches? Feed the specs to your LLM compiler. It generates optimized kernels while NVIDIA's engineers are still scheduling meetings. Competitor's chip looks promising? The compiler handles it. The software moat that took two decades to build gets crossed in months.

Who Actually Executes This

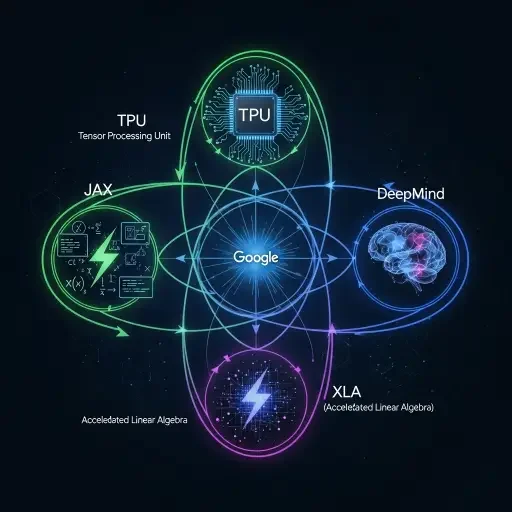

Google has all the pieces already assembled. TPUs give them freedom from CUDA's gravity well. JAX provides a functional programming model that compilers love. XLA already auto-optimizes across backends. DeepMind built AlphaCode. They have the audacity to break things and the institutional memory of disrupting Microsoft's developer tools dominance. The play is obvious: make JAX plus XLA the new standard—it's already more elegant than PyTorch for research—then add LLM-powered compilation targeting any hardware. Developer experience improves because you stop writing kernels; the AI does it. Performance matches or exceeds hand-tuned CUDA because LLMs explore optimization spaces humans can't.

AMD and Intel could license similar technology or build it themselves. Their hardware is competitive; their software problem becomes solvable when compilers write themselves. Startups like Groq, Cerebras, and Tenstorrent need differentiation. LLM-native compilation stacks are their path to software parity without hiring 1,000 CUDA experts.

NVIDIA faces an existential bind. They cannot easily pivot to this model without triggering three catastrophes simultaneously: admitting CUDA is obsolete destroys their moat, the 1,000-plus engineer CUDA organization whose expertise becomes worthless will resist institutionally, and customers who bet everything on CUDA will panic. Fresh competitors starting with modern paradigms have structural advantages over incumbents doing incremental evolution. It's the innovator's dilemma at planetary scale.

The Phase Transition Timeline

This isn't incremental competition—it's paradigm shift. The old world runs on human experts writing kernels, 17 years of accumulated tribal knowledge, hardware-specific optimization done manually, and CUDA's moat looking deep and impassable. The new world runs on LLMs writing kernels better than humans, hardware specifications plus compute graphs producing optimal code automatically, new architectures achieving parity in months rather than years, and CUDA's accumulated knowledge becoming irrelevant the way assembly language optimization expertise became irrelevant when optimizing compilers matured.

The timeline compresses uncomfortably fast. Eighteen to thirty-six months until LLM-powered compilers reach "good enough" for most workloads. Three to five years until new entrants achieve software parity using AI-generated optimization. Five to seven years until CUDA looks like COBOL—still widely deployed, clearly obsolete, everyone planning migration but nobody wanting to execute first.

What NVIDIA Should Do

The bold move would be acknowledging CUDA as legacy infrastructure, building LLM-native compilation infrastructure from scratch, open-sourcing it to become the new standard, and competing on hardware innovation rather than software lock-in. This would be strategically brilliant and politically impossible.

What they'll probably do instead: incremental CUDA improvements, defending the moat, and getting disrupted by someone willing to burn the bridges that NVIDIA cannot abandon. The pattern is familiar from every platform transition in computing history. Dominant players rarely execute their own creative destruction. They defend yesterday's advantages until market forces make the decision for them.

The question isn't whether NVIDIA's dominance faces challenge. The question is whether they'll recognize the phase transition before someone else eats their lunch. Because the next generation of GPU computing won't climb out of CUDA's gravity well through years of accumulated expertise and hand-optimized kernels. They'll build something new entirely, with AI writing the code that humans could never optimize as well. And when that happens, 17 years of accumulated advantage becomes 17 years of technical debt that must be serviced while competitors start fresh.

The moat becomes the prison. The fortress becomes the constraint. And the paradigm shift—visible to anyone willing to see it—renders obsolete everything that came before.

Sources

Analysis based on industry trends in GPU computing, compiler technology, and AI-driven code generation