The Arctic, once a map-checked backwater for climate scientists and the occasional oil prospect, has discovered a new weather system: signals. The China-US space race has migrated north, not just in bragging rights or orbital trajectories but in the architecture of power itself. Antenna farms—fields of parabolic mirrors and high-gain dishes set against ice and wind—are sprouting along coastlines and inland perches, stitching together weather satellites, deep-space beacons, and the networks that move data, faster and more securely, than ever before. This is not a mere supply chain story; it is a strategic deforestation of uncertainty, a deliberate pruning of the unknown through dense networks of reception.

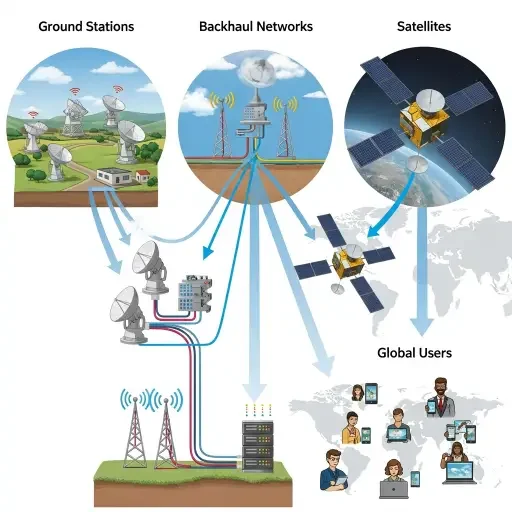

What makes the Arctic boom different from prior space infrastructure narratives is how it blends three functions into a single lattice: meteorology and climate monitoring, optical and radio astronomy, and secure communications for satellites and launch operations. In a world where timeliness becomes a decision variable—where a minute’s delay can cascade into an economic or strategic disadvantage—nations invest not merely in rockets but in ground truth: the weather that frames launch windows, the orbital debris that threatens reliability, the timing of signals that synchronize data across hemispheres. The result is a “multi-use corridor” that reframes the Arctic as a high-value data corridor rather than a mere corridor of ice.

The United States, along with its allies, treats Arctic antennas as critical infrastructure. The logic is not simply to be first to receive a signal but to command the reliability and scope of that signal. In practical terms, a handful of refurbished Cold War sites are retooled to support modern phased-array operations, while new sites are sited with a dual purpose: weather intelligence for early-warning of storms that could disrupt global shipping lanes, and radio astronomy for tracking near-Earth objects that might otherwise surprise planners. The Chinese approach mirrors this pragmatism but injects a different rhythm: more centralized funding, more rapid deployment cycles, and a willingness to capitalize on local expertise and private-public partnerships to scale capacity quickly.

Economically, the Arctic antenna boom is a microcosm of the broader “signal economy.” The capital involved is not a single launch program; it is a distributed network of land leases, subsurface rights, power agreements, fiber backhaul, and maintenance contracts that turn a cold shoreline into a manufacturing belt for information. It is not a glamorous frontier; it is a calculated one—where every installation is tested against the same triad: uptime, resilience, and security. The most interesting dynamic is not the size of the dishes but the quality of the data pipelines that connect them. Good pipes can translate a climate forecast into a trading edge. Secure pipes can turn a political pledge into a contractual guarantee.

This is where policy and business intersect with existential risk. The Arctic sits at a geopolitical crossroads with a fragile ecology. Local communities, Indigenous groups, and regional economies depend on those ecosystems—yet they also stand to benefit from improved forecast accuracy, new scientific collaboration, and the potential for technology transfer. The policy question is not only about who controls which antenna but who shares what data, how it is governed, and how to prevent an escalation of risk in a region already strained by meltwater, permafrost thaw, and rising ship traffic. In this calculus, openness and interoperability become competitive advantages. A network that can be audited, verified, and quickly reconfigured earns trust and reduces miscalculation—precisely the sort of governance edges that investors and policymakers say they crave.

For investors, the Arctic frontier offers both caution and lure. The capex is uneven, but the throughput potential—forecast, real-time, and archival—appears asymptotically valuable. The risk profile tracks political stability, climate resilience, and the fragility of supply chains that run on undersea cables and satellite telemetry. Yet the reward, if well harnessed, is a data moat: a network that can withstand shocks, seasonality of daylight, and the rough economics of northern logistics. In a world where information parity is sought with the same intensity as ballistic parity once was, the Arctic becomes the place where a new balance of power is negotiated—not with missiles, but with signals.

The practical takeaway is understated audacity: commit not just to one mega-project but to a portfolio of multi-use antenna farms, with modular, scalable architectures. Embrace modularity—phased deployments that can be upgraded as demands shift from meteorology to quantum communications, or from orbit-pinging radar to hyperspectral sensing. Build redundancy into the ground network as a line-item feature, not an afterthought, so that a single storm or a single satellite hiccup does not cascade into a governance crisis or a market shock.

The new Cold War frontier, then, is less about who can shoot further than whom and more about who can hear better and faster. The Arctic’s antenna farms are becoming the heartbeat of that capability, beating out a tempo that will shape weather, commerce, and cognition for decades to come.

Conclusion, in brief: the Space Race with China has ducked into the Arctic valley, where signals become strategy and infrastructure becomes influence. If the old frontier promised orbit, the new frontier promises continuity—signals unbroken, from ice to inbox, from sunlit data windows to night-long spectrometry. The stakes are not purely national security; they are the articulation of a reliable, scalable information regime that can guide markets, weather, and policy through the uncertain currents of a multipolar era.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

New reportage from Arctic research posts, defense analysts, satellite industry briefings, and open-source policy white papers; triangulated with commercial filings and expert interviews.